The Wild Science of Sourdough Starters

A few days ago, I mixed flour and water in a jar and left it on my counter.

That’s it.

No commercial yeast.

No additives.

No guarantees.

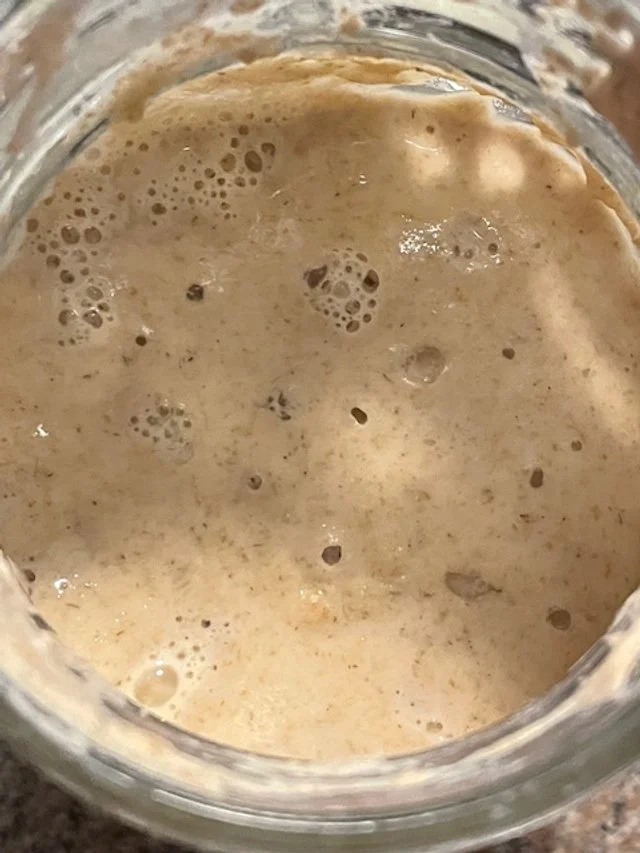

Within a day or two, that quiet mixture began to change. Tiny bubbles formed along the sides of the jar. The smell shifted from raw flour to something tangy and alive. It rose, fell, and reorganized itself in ways that felt almost intentional. In ways that were truly alive.

This is how every sourdough starter begins. Not as a recipe, but as an invitation into a different world. One we can only truly see under a microscope.

What a Sourdough Starter Actually Is

A sourdough starter is a living culture made up of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. These microorganisms already exist all around us. They live on grain, in the air, on our hands, and on our kitchen surfaces.

When flour and water are mixed and fed regularly, those microorganisms wake up.

Over time, they form a stable ecosystem capable of making bread rise, developing complex flavors, and preserving dough naturally. Unlike commercial yeast, which is designed to work quickly and predictably, a sourdough starter operates on its own timeline. It responds to its environment. It adapts. It is less a tool and more a partnership.

The Microbiology Happening in the Jar

What makes sourdough so fascinating is that it isn’t powered by a single organism. It’s a collaboration. A community, of sorts.

Wild yeast consumes sugars in the flour and produces carbon dioxide, which creates lift in bread. Lactic acid bacteria produce organic acids that shape flavor, strengthen dough structure, and influence digestibility.

These organisms don’t compete in the way we might expect. Instead, they create conditions that support each other. The bacteria acidify the environment in a way that favors certain yeast strains. The yeast, in turn, helps keep the system active and fed.

In the early days of a starter, things can feel chaotic. It might bubble aggressively one day and seem lifeless the next. It might smell fruity, sour, sharp, or vaguely unpleasant. This isn’t failure. It’s succession. Every culture is different. Its needs are different. It lives and breathes and acts accordingly to its own specific needs.

Just like in natural ecosystems, different microorganisms appear first, then give way to others better suited to the environment being created. Stability comes later.

Why No Two Starters Are the Same

Even when two starters begin with the same flour and water, they don’t stay identical for long.

Temperature, feeding schedule, hydration level, flour choice, and geography all influence which microorganisms thrive. Over time, a starter becomes specific to its place and its caretaker. In this way, a starter is very much a pet. We all nurture and care for them differently. They all have their own personalities, mannerisms, and schedules.

In other ways, sourdough starters are records. They hold information about where they live and how they are treated. A starter fed patiently and consistently behaves differently than one fed erratically or rushed along. This starter I’ve created in my kitchen would become a whole different culture in someone else’s. Every environment is different. Every sourdough culture is it’s own unique network of living organisms collaborating together.

There’s something deeply grounding about that. Bread doesn’t just reflect technique. It reflects care, collaboration, and celebration of differences.

What Starting a Starter Teaches Us

Starting a sourdough starter is a reminder that some processes can’t be forced.

You can’t rush fermentation by wanting it harder. You can’t control outcomes by micromanaging every variable. All you can do is show up, feed consistently, observe honestly, and respond to what’s actually happening instead of what you wish were happening.

That lesson applies far beyond baking.

Learning, growth, and community all work the same way. They take time. They require attention. And they thrive when we make space for them to develop naturally instead of demanding immediate results.

If sourdough has ever felt intimidating, I hope this reframes it. You’re not mastering a technique. You’re tending a relationship. You’re learning the needs of a whole group of organisms.

This kind of slow, curious baking is at the heart of what I teach through Breaducated. Bread is never just bread. It’s science, history, culture, and care, all happening quietly on your kitchen counter.

And sometimes, the most fascinating classroom is a jar of flour and water, doing its thing.